Genesis 38 lesson

Location

- Union Church of San Salvador

Date

- June 13, 2024

Lead Class Instructor

- Theodore Jedlicka

Facilitator

- Jaime Montoya

Scripture quotations

All Scripture quotations outside of references from bibliography, unless otherwise indicated, are taken from the Holy Bible: New International Version®. NIV®. Copyright © 1973, 1978, 1984 by International Bible Society. Used by permission of Zondervan. All rights reserved.

Table of contents

- Levirate marriage in ancient Israelite society

- Even if God did not institute levirate marriage, why does he condone it?

- Honorability and righteousness versus economic self-interest

- Where did Judah find his wife? (38:1-2)

- Wicked associations resulting in spiritual contamination (38:1-2, 12, 20-22)

- Giving names to each of their children (38:3-5)

- Why did Judah fear that Shelah could experience the same fate as his brothers? (38:11)

- Reputation with men versus good standing with God (38:12-23)

- What kind of prostitute did Tamar pretend to be? (38:21)

- Did God also kill Shelah? (38:26)

- Pattern of second son being greater than the firstborn (38:27-30)

Levirate marriage in ancient Israelite society

This custom or law was used in ancient Israelite society “to perpetuate the line of a man who died without offspring.” (Encyclopædia Britannica, n.d., levirate).

Weisberg (2009) explains that the Israelites did not invent levirate, but they adapted it to their needs. She provides reasons that reveal why it is not surprising that Israelite society practiced levirate:

- Continuity of the family and preservation of familial land were important.

- Inheritance was patrilineal.

- Wives were not recognized as their husband’s heirs. (Chapter 1)

Levirate marriage “was designed to prevent extinction of the family name and property” (Nelson, 2017, p. 351). According to Deuteronomy 25:5-10, its primary goal was “to provide the deceased with an heir.” (Weisberg, 2009, Chapter 2). The text acknowledges that it is possible that “the man does not want to marry his brother’s [widowed] wife” (Deuteronomy 25:7, Amplified Bible). Weisberg (2009) says that based on this Deuteronomy passage, the man is not obliged to offer an explanation, but he could simply say, “I do not want to marry her”, even when that would be “a refusal to honor his obligations to his brother”. Weisberg provides an interpretation that rationalizes why a man might refuse to marry his brother’s widow:

One could argue that levirate marriage is a completely altruistic act on the part of a brother. A man has little or nothing to gain and a great deal to lose by providing his brother with a posthumous heir. The death of a childless man would result in larger portions of the paternal estate going to the surviving brothers. Levirate marriage, if “successful,” results in the original distribution of property being maintained. Furthermore, the “loss” incurred by the levir comes through a child he himself has fathered; the levir is disinherited through his own actions! The only incentive Deuteronomy offers the levir is couched in negative terms; by agreeing to perform levirate marriage, he spares himself -and his descendants- public humiliation. (Chapter 2).

Three passages in the Old Testament mention levirate marriage: Genesis 38, Deuteronomy 25, and Ruth. In the New Testament, the Sadducees quoted levirate marriage when they came with a question to Jesus, as described in Matthew 22:23-32, but they were quoting the passage in Deuteronomy 25:5-10.

Even if God did not institute levirate marriage, why does he condone it?

Dean & Ballinger (n.d.) explain that levirate marriage was designed to protect childless widows by providing a source of income for them. In addition, levirate marriage law was designed to preserve and protect inheritance (The Levirate Marriage Custom).

Can imperfections be found in the levirate marriage custom/law? Yes, they can. Is God guilty of those imperfections? No, He is not. An example of an imperfect solution that God allowed even in the Mosaic legal system is divorce. Jesus explained in Matthew 19:8 that the original and perfect design of God did not include divorce. But the sin and imperfections of human beings made it necessary for God to allow divorce under some circumstances: “Moses permitted you to divorce your wives because your hearts were hard. But it was not this way from the beginning.” Similarly, when God created Adam and Eve, death did not even exist. The Fall produced death, which resulted in the possibility of a woman to become a widow. Inheritance rights and the continuity of a family line were at risk of being lost. An imperfect solution to the problem was regulated in the Law of Moses in the form of levirate marriage (Deuteronomy 25:5-10).

The imperfect solutions (levirate marriage and divorce) to big problems (death and adultery) should not be used as arguments to blame God for the countless big human problems. Contrary to that, the righteous reaction should be to realize that the solutions provided in the Law of Moses are imperfect and temporary. The final, permanent, and perfect solution is in Jesus Christ. The contrast between the Old Covenant represented by the Law of Moses, and the New Covenant revealed in Jesus, is thoroughly explained in the book of Hebrews. This truth is explicitly stated in Hebrews 8:7: “For if there had been nothing wrong with that first covenant, no place would have been sought for another.”

Honorability and righteousness versus economic self-interest

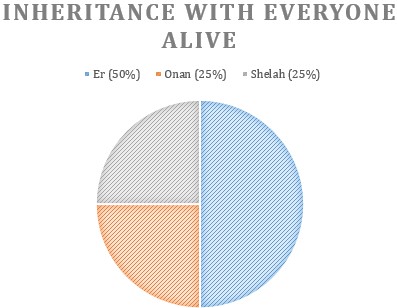

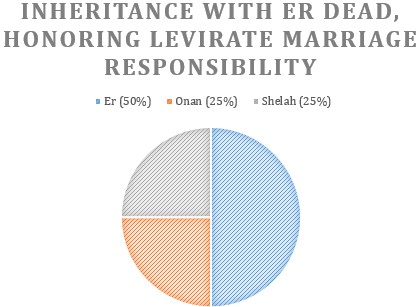

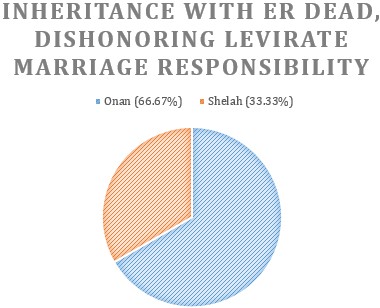

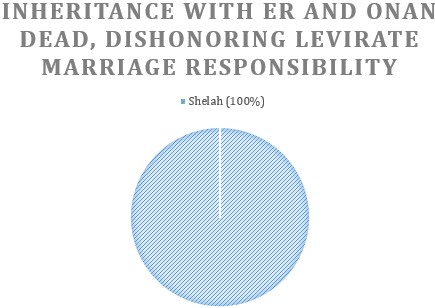

Frymer-Kensky (n.d.) provides a financial explanation of what could have motivated Onan to forsake his levirate marriage responsibility:

According to inheritance customs, the estate of Judah, who had three sons, would be divided into four equal parts, with the eldest son acquiring one half and the others one fourth each. A child engendered for Er would inherit at least one fourth and possibly one half (as the son of the firstborn). If Er remained childless, then Judah’s estate would be divided into three, with the eldest, most probably Onan, inheriting two thirds. Onan opts to preserve his financial advantage and interrupts coitus with Tamar, spilling his semen on the ground. For this, God punishes Onan with death, as God had previously punished Er for doing something wicked. (Tamar: Bible).

The following pie charts provide a way to visualize the distribution of the inheritance in different scenarios presented in Genesis 38:

Where did Judah find his wife? (38:1-2)

Shua, whose name means “prosperity” (Zondervan, 2015, šûa), was the father of the unnamed daughter who married Judah. Shua was a Canaanite and the city where Judah and Shua’s daughter met is Adullam.

Adullam is one of the thirty-six cities mentioned in Joshua 12 as part of the list of the kings of the “list of the kings of the land that Joshua and the Israelites conquered” (Joshua 12:7-24). David escaped to a cave in Adullam when he was hiding from Saul who wanted to kill him (1 Samuel 22:1).

Wicked associations resulting in spiritual contamination (38:1-2, 12, 20-22)

Waldrip (n.d.) emphasizes that Judah made a poor spiritual decision with catastrophic consequences by establishing a long friendship with Hirah, a nonbeliever. Judah married a Canaanite wife and when she died, Hirah was again with Judah when his time of mourning was ended. He is also mentioned as a friend of Judah in charge of sending a young goat to Tamar the “prostitute”. It can be implied that Judah and Hirah were friends for a long time (Judah’s friend Hirah).

By marrying the daughter of and idolater, Judah would have profaned the holy desires of God and betrayed the way of his father Jacob, a sin portrayed in Malachi 2:11 (Kadari, n.d., Shua's daughter: Midrash and Aggadah):

Judah has been unfaithful. A detestable thing has been committed in Israel and in Jerusalem: Judah has desecrated the sanctuary the Lord loves by marrying women who worship a foreign god.

Giving names to each of their children (38:3-5)

Zonvervan (2014) asks: “An absentee father? Where was Judah in the naming of his children?” The suspicion comes from the fact that Judah named his firstborn Er, but the one who gave names to Onan and Shelah was Shua (Judah’s wife). It appears as if Judah was neglecting his duties as a father. (Genesis 38:4-5).

Zondervan (2015) provides the meaning of the names of each of Judah’s sons:

- Er: “watchful, watcher” (ʽēr)

- Onan: “powerful, intense” (’ônān)

- Shelah: “missile [a weapon], sprout” (šēlâ)

Why did Judah fear that Shelah could experience the same fate as his brothers? (38:11)

Walton (2001) offers two possible reasons of why Judah feared that his third son Shelah might also die, following the death pattern of Judah’s first and second sons, Er and Onan:

- Recognition that the deaths of his sons may well be punishment for his treatment of Joseph give plausibility to his fear that his last son, Shelah, will meet the same fate as his brothers.

- Women who seemed prone to become widows were in danger of being suspected of witchcraft. (Judah’s problem: Genesis 38:1 – 11).

In case of the second of the options above being the true reason for Judah’s fear, it is plausible to believe that Judah was blaming Tamar as responsible for the deaths of his first two sons Er and Onan, possibly trying to ignore or being blind to the fact that his sons who died were wicked before God.

Evans (2019) believes that Judah’s refusal to arrange marriage between Shelah and Tamar seemed to be because Judah blamed Tamar for the deaths of Er and Onan (Genesis 38:11).

Reputation with men versus good standing with God (38:12-23)

In terms of his name or reputation, Judah did not seem to be proud of what he did concerning having a sexual encounter with someone who was, in his mind, a temple prostitute. In Genesis 38:23, English Standard Version, Judah says: “Let her keep the things as her own, or we shall be laughed at.” Henry (1811) provides two possible interpretations for “lest we be shamed” in verse 23:

- Lest his sin should come to be known publicly, and be talked of. Fornication and uncleanness have ever been looked upon as scandalous things and the reproach and shame of those that are convicted of them. Nothing will make those blush that are not ashamed of these.

- Lest he should be laughed at as a fool for trusting a strumpet with his signet and his bracelets. He expresses no concern about the sin, to get that pardoned, only about the shame, to prevent that. Note, There are many who are more solicitous to preserve their reputation with men than to secure the favour of God and a good conscience; lest we be shamed goes further with them than lest we be damned. (Genesis 38:12-23).

Ironically, Judah seemed to be concerned about his reputation. (Thomas Nelson, 2002, Genesis 38:23).

As a lesson to learn from the story, after his sexual encounter with Tamar, Judah seemed more interested in protecting his reputation with men than repenting to have a good standing with God. Fortunately, unlike Er and Onan, it can be inferred that Judah repented from his sin once it was exposed. He admitted being wrong, and abandoned sexual sin with Tamar, as expressed in Genesis 38:26: 'Judah recognized them and said, “She is more righteous than I, since I wouldn’t give her to my son Shelah.” And he did not sleep with her again.'

What kind of prostitute did Tamar pretend to be? (38:21)

Crossway Bibles (2005) explains that the Hebrew used in Genesis 38:21 when referring to Tamar as a “cult prostitute”, means “sacred woman; a woman who served a pagan deity by prostitution.” (Genesis 38:21, p. 32).

Tamar “dressed and acted like a Canaanite temple prostitute” (Thomas Nelson, 2017, p. 79).

Did God also kill Shelah? (38:26)

The last time in Genesis 38 where Shelah is mentioned is in verse 26. Nonetheless, Shelah is mentioned in 1 Chronicles 4:21-23, including the list of his sons. This reveals that Shelah eventually married and was not killed by God the way his brothers Er and Onan were. It is interesting to notice that Er was the name of one of Shelah's sons, presumably the firstborn because he is listed first in 1 Chronicles 4:21. It was not Shelah’s fault that he did not practice levirate marriage with Tamar. It could be a possibility that naming his son Er, was a way to honor his deceased brother Er. Regardless, the Messianic genealogy comes from Judah and Tamar, not from Shelah.

Pattern of second son being greater than the firstborn (38:27-30)

As Tamar was giving birth, Zerah came out first by putting out his hand. Nonetheless, Zerah drew back his hand and his brother Perez came out. They were twin boys.

Perez's name originates from the midwife's exclamation that he had made a “breakthrough”. No reason is provided for Zerah's name (Tan, 2017, p. 113).

The pattern of “the second son being greater than the firstborn” is found several times in the Bible. For example, Cain and Abel, Ishmael and Isaac, Esau and Jacob, and Manasseh and Ephraim.

The genealogy of Zerah, whose name means “dawning, shining or flashing [red or scarlet] light” (Zondervan, 2015, zeraḥ), appears in 1 Chronicles 2:6. The sons of Perez, whose name means “breaking out” (Zondervan, 2015, pereṣ), are mentioned in 1 Chronicles 2:5.

1 Chronicles 2:7 mentions Karmi as the father of Achar. Joshua 7:1 also refers to both Karmi and Achar, even though in Joshua the name is spelled Achan (using the New International Version). Both passages are referring to the same persons. It is also revealed in Joshua 7:1 that Achar comes from Zerah, son of Judah. Sadly, Achar’s sin described in Joshua 7, produced God’s fierce anger and the people of Israel stoned him to death as God’s judgement against Achar.

The line of Christ is found in the genealogy of Perez, as revealed in 1 Chronicles 2:5, 9-16.

References

Crossway Bibles. (2005). The Holy Bible. Life Discovery Bible. ESV.

Dean, R., & Ballinger, J. (n.d.). The Levirate Marriage Custom. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://kukis.org/Doctrines/leviratemarriage.htm

Encyclopædia Britannica. (n.d.). levirate. Retrieved June 7, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/levirate

Evans, T., (2019). CSB Tony Evans Study Bible. https://www.amazon.com/CSB-Tony-Evans-Study-Bible-ebook/dp/B07ZPKY6TX/

Frymer-Kensky, T. (n.d.). Tamar: Bible. Retrieved June 7, 2024, from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/tamar-bible

Henry, M. (1811). An Exposition of the Old and New Testament. https://www.google.com.sv/books/edition/An_Exposition_of_the_Old_and_New_Testame/fg8aY9ZqSMYC?hl=es-419&gbpv=1

Kadari, T. (n.d.). Shua's daughter: Midrash and Aggadah. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/shuas-daughter-midrash-and-aggadah

Walton, J. (2001). The NIV Application Commentary: Genesis. https://www.amazon.com/Genesis-Application-Commentary-John-Walton-ebook/dp/B004FPZ29A/

Tan, B. (2017). Tamar is Righteous, but Judah is Not: A Narrative Analysis of Genesis 38. A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Theology. Singapore Bible College. Retrieved June 13, 2024, from https://www.academia.edu/33060247/Tamar_Is_Righteous_but_Judah_Is_Not_A_Narrative_Analysis_of_Genesis_38

Thomas Nelson. (2002). NKJV New Spirit-Filled Life Bible

Thomas Nelson. (2017). The King James Study Bible.

Waldrip, J. (n.d.). Judah’s friend Hirah. Retrieved June 11, 2024, from https://calvaryroadbaptist.church/sermon.php?sermonID=5

Weisberg, D. (2009). Levirate Marriage and the Family in Ancient Judaism. https://www.amazon.com/Levirate-Marriage-Family-Ancient-Judaism-ebook/dp/B07PQ1ZK57/

Zondervan. (2015). NIV Exhaustive Concordance Dictionary. https://www.biblegateway.com/plus/

Zondervan. (2014). NIV First-Century Study Bible. https://www.amazon.com/NIV-First-Century-Study-Bible-eBook-ebook/dp/B00MTB1YSU/